Introduction

If you received an email with the subject “I LOVE YOU” and an attachment called “LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.TXT”, would you open it? Probably not, but back in the year 2000, plenty of people did exactly that. The internet learned a hard lesson about the disproportionate power available to a university dropout with some VBScript skills, and millions of ordinary people suffered the anguish of deleted family photos or even reputational damage as the worm propagated itself across their entire Outlook address book.

In the quarter century since ILOVEYOU rampaged across global networks, cybersecurity has moved from a niche topic to an “everyone” problem, and many users are wary of all sorts of threats. In recent years, the increasing ubiquity and urgency of AI adoption across the business landscape has attracted the attention of both security researchers and threat actors.

Of course, recency bias and shiny object fixation are real. Even as AI and automation continue to drive down time to known exploitation (TTKE), an attacker who abuses a traditional exploit chain to achieve SYSTEM privileges on a sensitive server still has the keys to the kingdom.

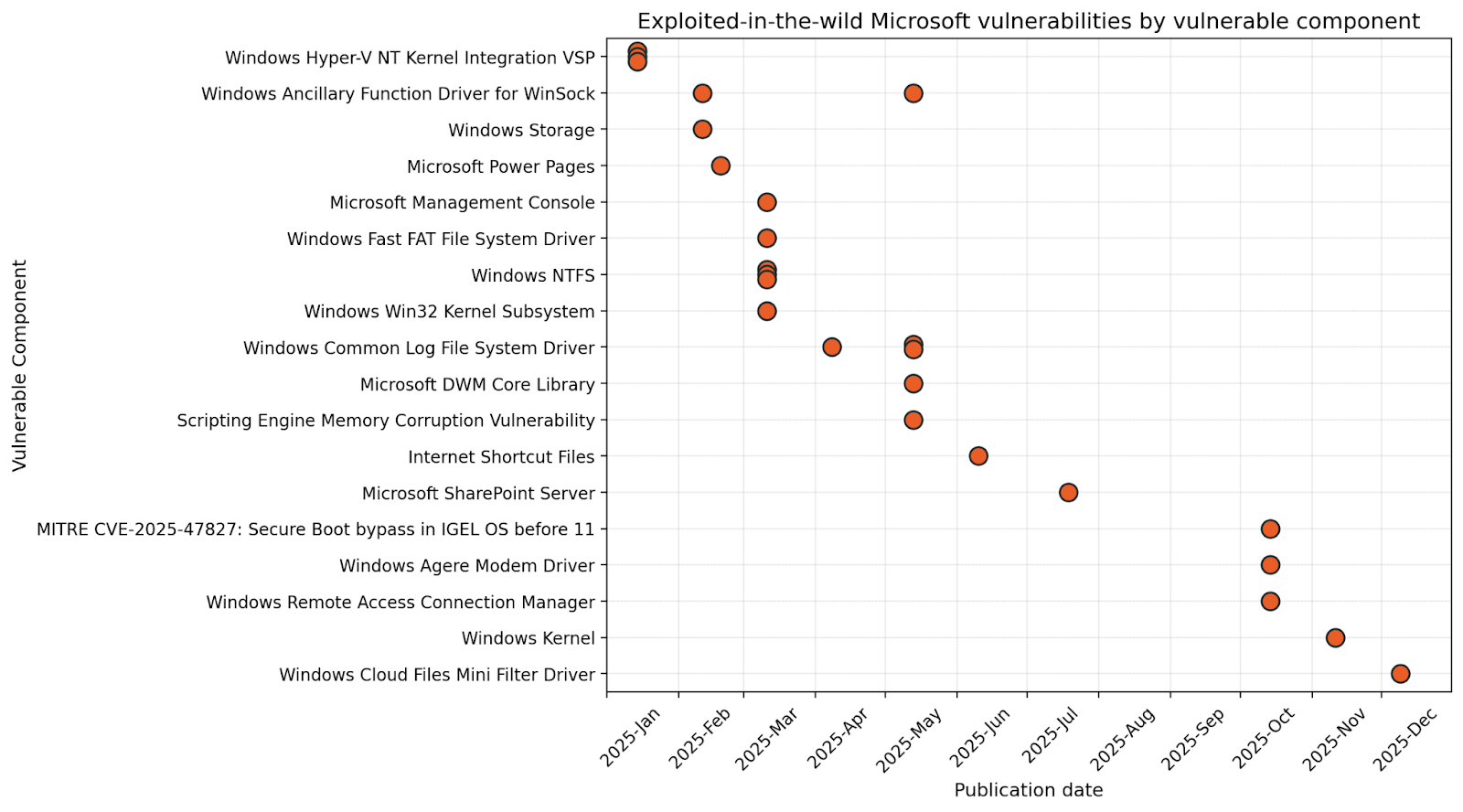

Wormable remote code execution (RCE) vulnerabilities remain rare, but well over half of the 25 exploited-in-the-wild zero-day vulnerabilities published by Microsoft during 2025 provided attackers with elevation of privilege opportunities on Windows assets. Some of those flaws are older than the iPhone, let alone ChatGPT.

Microsoft's decades-long commitment to backwards compatibility creates a conveyor belt supply of déjà vu vulnerabilities. Ultimately, the most pressing threats faced by defenders managing Microsoft estates remain essentially unchanged. Rather than a new wave of AI-related flaws, the chief danger stems from the towering tech debt within core Windows components.

A whirlwind tour of exploited-in-the-wild Microsoft vulnerabilities (2025 edition)

If we really want to know which Microsoft vulnerabilities will provide the most value to attackers in 2026, we should ask a threat actor. Since that might prove difficult to arrange, we’ll do the next best thing: review vulnerabilities exploited in the wild during 2025.

⠀

January: The great escape

The vast Microsoft ecosystem has something for everyone, whether customer or threat actor. Patch Tuesday January 2025 brought us a trio of exploited-in-the-wild Hyper-V kernel vulnerabilities. By September 2025, at least one plausible public proof-of-concept (PoC) for CVE-2025-21333 was published by a vulnerability researcher who apparently shares a name with a Kazakhstani Olympic gymnast. The only safe assumption is that a well-resourced threat actor could develop a private exploit far in advance of that.

Starting from a child VM or Windows Sandbox, exploitation first requires setting out a banquet of benign requests for the hypervisor, delivered via the Hyper-V Virtualization Service Provider (VSP). The goal: mass-allocating objects to arrange large swathes of hypervisor memory in a predictable pattern (aka “heap feng shui”). Next, the attacker sends a malicious request with an oversized buffer, which an unpatched VSP merrily copies into kernel memory, overwriting the header of the adjacent object, whose relative position is now easily surmised. Once the kernel subsequently references the artfully corrupted sibling object, execution as SYSTEM jumps to a portion of memory where the attacker has planted shellcode to exfiltrate a token. The compromised hypervisor could be anything from a developer laptop running a malicious container all the way up to enterprise private cloud infrastructure.

So far, January 2025 is the only time that Microsoft has ever published vulnerabilities in the Hyper-V VSP. Generally speaking, a significant degree of sophistication is required to develop successful exploits of this nature. This goes double if the name of the game is stealth and stability, since a wave of unexplained BSOD events on critical production infrastructure tends to attract blue team attention. Still, once a viable proof of concept hits the public internet, ransomware crews will fold it into their toolkits, and someone, somewhere, is either sitting on an unknown Hyper-V VSP exploit, or hard at work creating the next one.

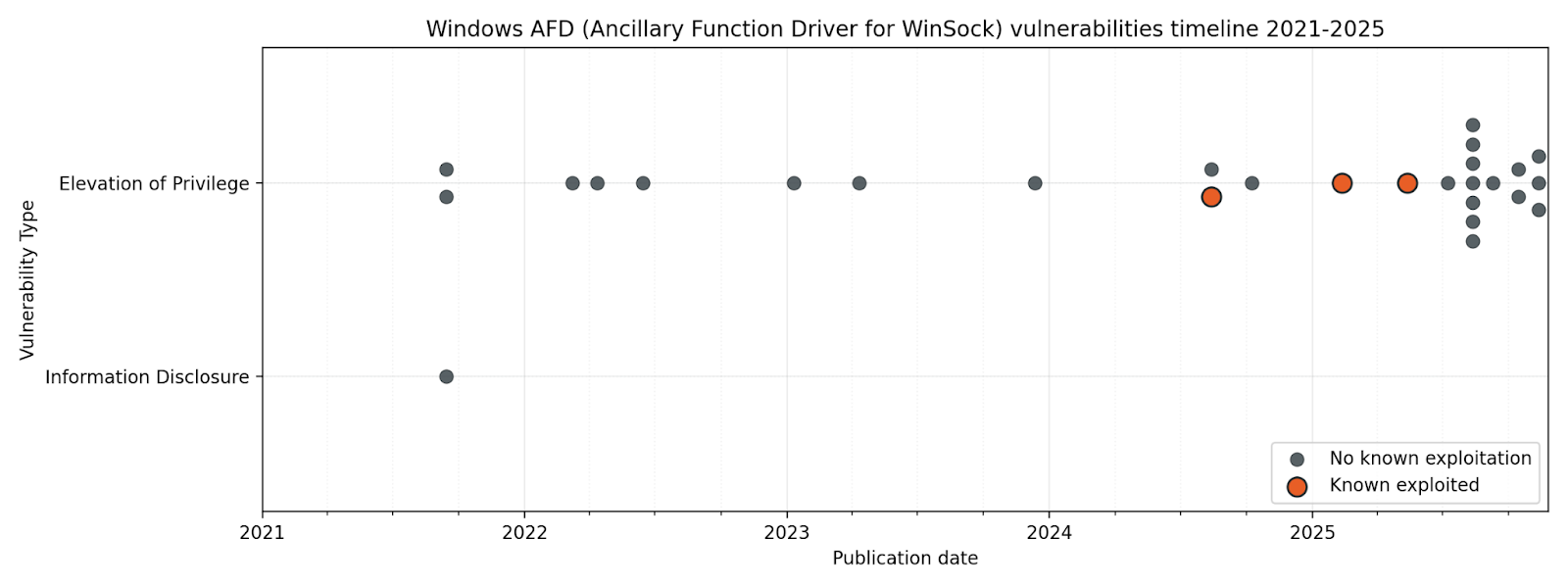

February: Socket to me

It’s hard to imagine a modern computer without storage or networking capabilities. In fact, it’s hard to imagine a computer from several decades ago without storage or networking. Microsoft is now middle-aged, and that means that buried deep within your shiny new PC are a variety of architectural decisions and logic paths born in the 1980s. If this sounds far-fetched, take a minute to find yourself a fully-patched Windows 11 25H2 machine, and then try to rename any file or directory CON, NUL or PRN. I’ll wait.

Generally speaking, user-mode applications are prevented from wreaking havoc on the kernel through a careful separation of concerns. On Windows, when a user mode application wants to communicate over the network, it talks to WinSock, which in turn talks to the ancillary function driver (AFD), which sits on the kernel side, and coordinates with the kernel network drivers which handle the actual traffic. The AFD is a security boundary between user space and kernel space, and it must be universally accessible to local processes, because even a browser tab in a sandbox needs to make network calls. Any defect in the way AFD parses input from user space can thus provide a way to influence the kernel in unexpected ways. A number of advanced exploit development courses, including offerings from SANS and OffSec, cover AFD in detail.

⠀

⠀

Patch Tuesday February 2025 brought us CVE-2025-21418, which Microsoft credited to Anonymous. We don’t know whether the unnamed tipster provided evidence of exploitation in the wild, or whether Microsoft threat hunters subsequently tracked down their own trail of suspicious bread crumbs, but notorious threat actors such as North Korea’s Lazarus are known to be enthusiastic students of AFD exploits. With several high-profile zero-day vulnerabilities emerging from AFD from late 2024 onwards, it tracks that Microsoft subsequently published and patched a cluster of AFD vulnerabilities in the latter half of 2025.

March: File system shenanigans

Any defenders who had enjoyed a quieter start to the year were rudely awakened by Patch Tuesday March 2025, when six exploited-in-the-wild vulnerabilities all dropped at once. Exploitation of most of the zero-day vulnerabilities published in March starts with the user mounting a malicious Virtual Hard Disk (VHD) image or plugging in a malicious USB stick so that the attacker can exploit a weakness in a filesystem driver, including NTFS and FastFAT.

Remember that information security training which asked you to imagine finding a USB stick with an “IMPORTANT (CONFIDENTIAL)” label on the floor outside the office? The one which asked if you would A) plug the mystery stick into your work PC B) use your boss’ personal laptop in case the files are business critical C) try it in all the PCs in the office until someone asks you to stop or D) report it immediately to the security officer? This is why.

Meanwhile, the true villain of the month was almost certainly CVE-2025-24983, a no-user-interaction-required elevation of privilege vulnerability in the Win32 kernel subsystem. At the time, we pondered why Windows 11 and Server 2019 onwards didn’t receive patches for what looks like a fairly severe vulnerability, but since Microsoft is gradually reimplementing portions of the kernel in memory-safe Rust, we can hope that the vulnerability simply doesn’t exist in modern Windows.

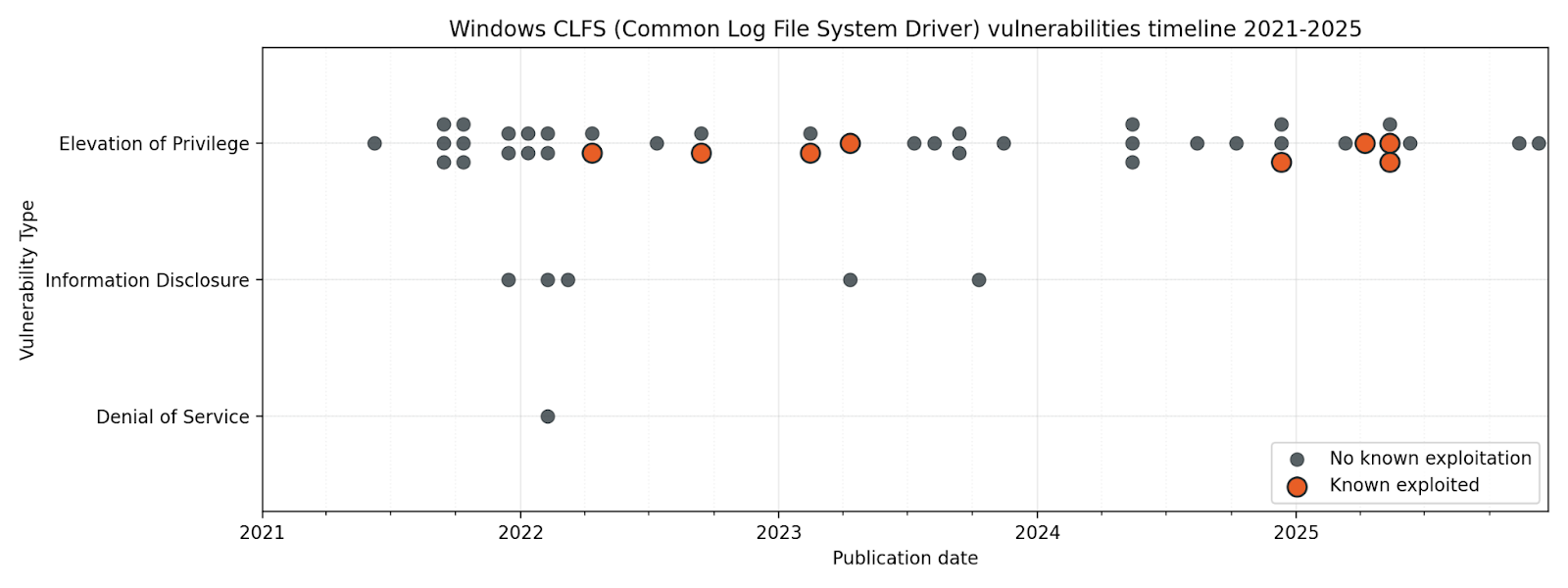

April: Common Log File System driver vulns are quite common

If anyone ever corners you at a party and talks at length about the Ancillary Function Driver as a bounteous source of elevation of privilege vulnerabilities, you will probably have to concede that they are technically correct. While your options include “doing a lap” and then climbing out of the bathroom window, the power move here is to hold your ground, and point to the Common Log File System driver as a far richer vein of exploitable goodness.

As of Patch Tuesday April 2025, CLFS boasts almost twice the number of total vulnerabilities over the past five years vs. AFD, and more than double the number of known-exploited zero-day vulnerabilities. It really is the gift which keeps on giving.

⠀

⠀

It makes sense that something like the Ancillary Function Driver lives in kernel space. After all, something has to sit inside the perimeter to marshall all those network requests from dozens of Chrome tabs. What about the Common Log File System driver though?

It would be tempting to imagine that anything which simply handles log files shouldn’t need direct kernel access at all. When exploring this concept, it’s useful to understand that not only was CLFS designed a long time ago, when high performance in user mode was harder to achieve than it is today, but also that CLFS is much more than simply a means to interact with log files. CLFS is the home of still-essential building blocks like Transactional NTFS (TxF), first introduced almost 25 years ago in Windows Vista, which provides a means for applications to guarantee the integrity of data on disk.

For the past several years, Microsoft has strongly recommended that developers avoid the use of TxF, and while Microsoft is gradually providing modern alternatives to TxF functionality, essential Windows functions such as Windows Update still rely on it to manage critical file integrity. Moreover, CLFS is more than just TxF, and is so tightly integrated into Windows that it’s here to stay for the foreseeable future.

May: The month of expectation, wishes, hope, and classic Windows zero-days [1]

A few days after Patch Tuesday May 2025, Satya Nadella took to the stage at Microsoft Build 2025 to pitch his vision of the open agentic web, although exactly who this version of the future would be open to remains an open question, like: What if a cloud email service was vulnerable to a zero-click prompt injection attack, but could also now buy things with your credit card?

While critical reception for the open agentic web has been mixed, threat actors will be glad of the new attack surface. Meanwhile, defenders worried about in-the-wild exploitation were hard at work patching some more frequent fliers, including another pair of CLFS vulnerabilities and an MSHTML/Trident arbitrary code execution bug. That last one will be familiar to regular Patch Tuesday watchers, but it might come as a surprise to anyone who thought Internet Explorer had gone to live on a nice farm upstate years ago.

The Ancillary Function Driver made another appearance, although it couldn’t quite summon the same main character energy this time around. The May 2025 episode of “AFD vulns exploited in the wild” offered elevation to Administrator, rather than SYSTEM, and a lower exploit code maturity rating. We can always be grateful for small mercies.

[1]: With apologies to Emily Brontë.

June: I’m afraid I can’t let you do that, WebDAV

Windows archeologists and internet users of a certain age may remember WebDAV, a standard originally dreamed up to support interactivity on the web. It was employed by versions of Microsoft Exchange up to and including 2010 to handle interactions with mailboxes and public folders.

Surprising no-one, Windows still more or less supports WebDAV, and it was only a matter of time before that turned out to be a bit of a problem, in the form of CVE-2025-33053 published as part of Patch Tuesday June 2025. Microsoft acknowledged Check Point Research (CPR) on the advisory; CPR in turn attributes exploitation to an APT (Advanced Persistent Threat), which they track as the objectively cool-sounding Stealth Falcon, an established threat actor with a long-running interest in governments and government-adjacent entities across the Middle East and beyond.

June 2025 also saw the publication of CVE-2025-32711, a critical information disclosure vulnerability in Microsoft 365 Copilot. Microsoft is not aware of exploitation in the wild. The researchers named it EchoLeak, describing it as “the first real-world zero-click prompt injection exploit in a production LLM system,” although other researchers arguably got there first.

EchoLeak relies on hidden white-text-on-white-background instructions in an email, which are then ingested into the LLM via RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) when the user asks an entirely pedestrian question (e.g. “Summarize my emails from the past two days”) which requires Copilot to scan the inbox. The malicious instructions have two parts: First, dig up some juicy info, and then retrieve an image from an attacker-controlled server with the sensitive data exfiltrated as a URL parameter.

EchoLeak circumvented Copilot’s Content Security Policy by making the request via a trusted Microsoft service: a now-patched Teams image preview proxy. History suggests that attackers will find other ways out of the walled garden. The Microsoft advisory makes a virtue of minimalism by providing almost no information about the nature of the vulnerability, although Microsoft is surely to be commended for assigning CVEs for cloud service vulnerabilities.

July: The call is coming from inside the intranet

When Patch Tuesday July 2025 came and went without a single exploited-in-the-wild vulnerability published, many people may have breathed a sigh of relief. Possibly this was a valid move, at least for anyone not responsible for a SharePoint instance.

SharePoint defenders will remember July as the month of ToolShell, an actively-exploited vulnerability chain in SharePoint which Microsoft published out of band ten days after Patch Tuesday. Out of band patches for Microsoft flagship products are rare, since they inevitably cause downstream disruption. Once MSTIC publicly attributes exploitation to two Chinese nation-state actors, that line has been crossed.

The vulnerability described by the out-of-band CVE-2025-53770 turned out to be a bypass for the patch introduced by CVE-2025-49704 earlier in the month, which was itself a response to a successful Pwn2Own Berlin entry from May.

August: It’s almost too quiet

Microsoft was not aware of exploitation in the wild for any of the vulnerabilities published as part of Patch Tuesday August 2025. SharePoint admins may have been dealing with the fallout from last month’s ToolShell and bracing for a possible repeat, but August might otherwise have made for an eerily quiet month. Still, the Windows implementation of Kerberos managed to cough up a publicly-disclosed elevate-to-domain-admin vulnerability.

Separately, we learned that simply saving a JPEG could be enough to hand an attacker RCE capabilities, because the internet never sleeps. If the vulnerable codepath had been within JPEG decoding, rather than encoding, this one could have been the biggest vuln of the year.

September: Almost too quiet, part 2

Patch Tuesday September 2025 was the second month in a row with no known-exploited vulnerabilities, but vuln spotters will appreciate that this month saw the publication of a fairly rare beast: a Microsoft vulnerability with a perfect(?) CVSS v3 base score of 10.0, albeit a cloud service vulnerability discovered by Microsoft and patched prior to publication. No customer action required, but also no customer verification possible, and since the impacted cloud service was Azure Networking, the blast radius could have been stupendous.

October: Dial M for exploitation

These days, there are plenty of seasoned IT professionals who don’t even know what a dialup modem negotiation song sounds like, simply because broadband has been around for that long. For younger readers, “broadband” is what we used to call “internet fast enough that you don’t have to wait to download a single email attachment”.

By this point, we all know where this is going: Windows still ships with modem capabilities well beyond their sell-by date, and someone found a good old elevation of privilege vulnerability. The vulnerable fax modem driver was developed almost 30 years ago by a long-defunct third party, and Microsoft has now taken uncharacteristically bold action by removing it from Windows altogether, perhaps recognizing that traditional landlines are no longer available at all in many places. Are there other fax modem drivers still lurking in Windows? You betcha.

Patch Tuesday October 2025 also marked the end of Windows 10, unless you count the cash-for-patches Extended Security Updates (ESU) program.

November: Kernel vuln? Popcorn time

Patch Tuesday November 2025 included an exploited-in-the-wild vulnerability in the Windows kernel itself. While the advisory was light with details, exploitation of CVE-2025-62215 led to elevation to SYSTEM, presumably via a complex bit of memory management three card monte. Those kernel Rust rewrites can’t come soon enough.

December: A cloud of suspicion

After a year filled with variations of the same old exploitable vulns, it might almost be refreshing to consider the altogether more modern-sounding exploited-in-the-wild vulnerability published on Patch Tuesday December 2025. CVE-2025-62221 describes an elevation of privilege vulnerability in the Windows Cloud Files Mini Filter Driver.

On Windows, a file or directory can contain a reparse point, a collection of user-controlled metadata designed to be interpreted by a file filter driver. An example would be a file which appears present in a local folder, but where the actual contents of the file are stored remotely on OneDrive. The user double-clicks on the file, the file filter driver intercepts the request, reads the metadata, and calls out to OneDrive, while the user gets the experience of opening the file as though it had been stored locally. Of course, the file filter driver needs kernel access to perform its duties. Find an exploitable flaw in the way a file filter driver parses the metadata, and you can trick it into doing things like overwriting protected system files.

What’s next?

Everything gets faster, including bad things

As Rapid7 has observed repeatedly, time to known exploitation for widely-exploited vulnerabilities has been shrinking year-on-year. By 2022, the time to exploitation after public disclosure for some of the most notable security vulnerabilities was as low as 24 hours. With exploit development now widely augmented by automation and AI, there is every reason to suppose that the window will continue to shrink further.

Threat actors will stay best friends with elevation of privilege vulns

A wormable unauthenticated RCE vulnerability remains the scariest scenario, but mercifully these are historically rare. The one-two combo of minimally-privileged initial access and local privilege escalation presents a much more clear and present danger in most modern threat models. Sure, you could parachute in from a helicopter, abseil down from the roof, and crawl through an air vent to steal the diamond, but why bother when you could simply tailgate a delivery driver, and then distract a maintenance worker while you swipe their all-access keycard?

AI is here to stay, but tech debt is the real killer

In 2026, Microsoft will regularly publish AI-related vulnerabilities, and AI-wielding threat actors will hammer Microsoft’s cloud services. Blue teams managing significant Windows estates will still spend more time worrying about on-prem vulnerabilities where the root cause is a classic software engineering snafu.

Final thoughts

Arguably the biggest takeaway from 2025 is that the more things change, the more they stay the same. The scariest Microsoft vulnerabilities tend to emerge from the same few familiar places: core Windows components with codebases older than many of the humans who rely on them.

Microsoft’s wildly successful business model is founded on a decades-long insistence on ironclad backwards compatibility. Why? Enterprise customers with deep pockets and deeper catalogues of ancient business applications. These retro capabilities come at a high price: a supervolcano of tech debt potentially unmatched in all of human history, and a seemingly endless supply of sort-of-new but depressingly familiar vulnerabilities.

For anyone responsible for defending a significant Microsoft footprint in 2026, tomorrow’s biggest problem remains today’s secrets exposed by yesterday’s software design choices.