I recently wrote a blog post on injection-type vulnerabilities and how they were knocked down a few spots from 1 to 3 on the new OWASP Top 10 for 2022. The main focus of that article was to demonstrate how stack traces could be — and still are — used via injection attacks to gather information about an application to further an attacker's goal. In that post, I skimmed over one of my all-time favorite types of injections: cross-site scripting (XSS).

In this post, I’ll cover this gem of an exploit in much more depth, highlighting how it has managed to adapt to the newer environments of today’s modern web applications, specifically the API and Javascript Object Notation (JSON).

I know the term API is thrown around a lot when referencing web applications these days, but for this post, I will specifically be referencing requests made from the front end of a web application to the back end via ajax (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) or more modern approaches like the fetch method in JavaScript.

Before we begin, I'd like to give a quick recap of what XSS is and how a legacy application might handle these types of requests that could trigger XSS, then dive into how XSS still thrives today in modern web applications via the methods mentioned so far.

What is cross-site scripting?

There are many types of XSS, but for this post, I’ll only be focusing on persistent XSS, which is sometimes referred to as stored XSS.

XSS is a type of injection attack, in which malicious scripts are injected into otherwise benign and trusted websites. XSS attacks occur when an attacker uses a web application to execute malicious code — generally in the form of a browser-side script like JavaScript, for example — against an unsuspecting end user. Flaws that allow these attacks to succeed are quite widespread and occur anywhere a web application accepts an input from a user without sanitizing, validating, escaping, or encoding it.

Because the end user’s browser has no way to know not to trust the malicious script, the browser will execute the script. Because of this broken trust, attackers typically leverage these vulnerabilities to steal victims’ cookies, session tokens, or other sensitive information retained by the browser. They could also redirect to other malicious sites, install keyloggers or crypto miners, or even change the content of the website.

Now for the "stored" part. As the name implies, stored XSS generally occurs when the malicious payload has been stored on the target server, usually in a database, from input that has been submitted in a message forum, visitor log, comment field, form, or any parameter that lacks proper input sanitization.

What makes this type of XSS so much more damaging is that, unlike reflected XSS – which only affects specific targets via cleverly crafted links – stored XSS affects any and everyone visiting the compromised site. This is because the XSS has been stored in the application's database, allowing for a much larger attack surface.

Old-school apps

Now that we’ve established a basic understanding of stored XSS, let's go back in time a few decades to when web apps were much simpler in their communications between the front-end and back-end counterparts.

Let's say you want to change some personal information on a website, like your email address on a contacts page. When you enter in your email address and click the update button, it triggers the POST method to send the form data to the back end to update that value in a database. The database updates the value in a table, then pushes a response back to the web application's front end, or user interface (UI), for you to see. This would usually result in the entire page having to reload to display only a very minimal amount of change in content, and while it’s very inefficient, the information would nonetheless be added and updated for the end user to consume.

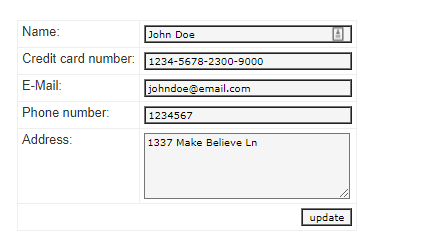

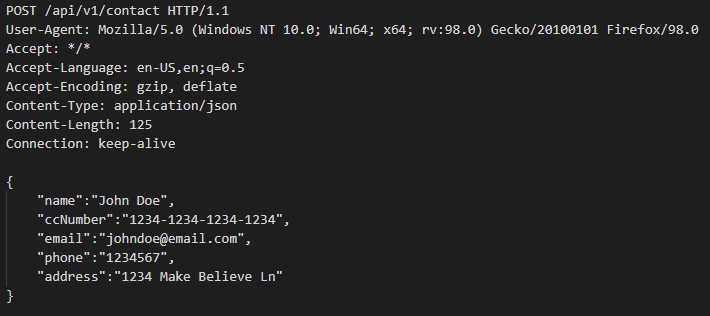

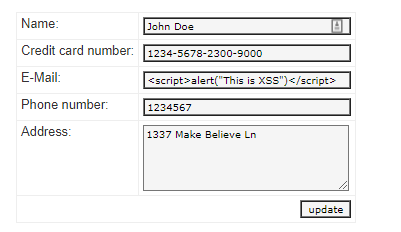

In the example below, clicking the update button submits a POST form request to the back-end database where the application updates and stores all the values, then provides a response back to the webpage with the updated info.

Old-school XSS

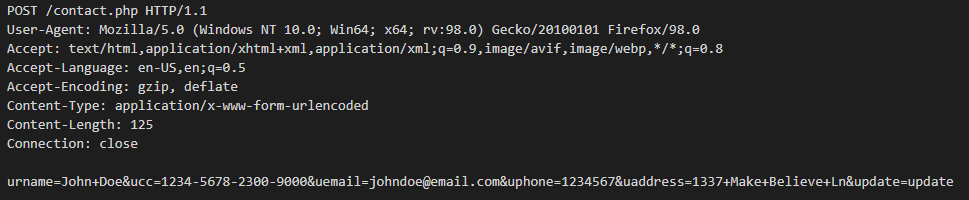

As mentioned in my previous blog post on injection, I give an example where an attacker enters in a payload of <script>alert(“This is XSS”)</script> instead of their email address and clicks the update button. Again, this triggers the POST method to take our payload and send it to the back-end database to update the email table, then pushes a response back to the front end, which gets rendered back to the UI in HTML. However, this time the email value being stored and displayed is my XSS payload, <script>alert(“This is XSS”)</script>, not an actual email address.

As seen above, clicking the “update” button submits the POST form data to the back end where the database stores the values, then pushes back a response to update the UI as HTML.

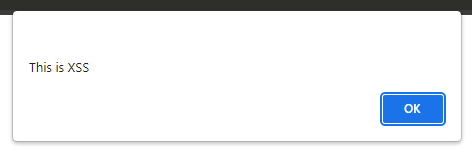

However, because our payload is not being sanitized properly, our malicious JavaScript gets executed by the browser, which causes our alert box to pop up as seen below.

While the payload used in the above example is harmless, the point to drive home here is that we were able to get the web application to store and execute our JavaScript all through a simple contact form. Anyone visiting my contact page will see this alert pop up because my XSS payload has been stored in the database and gets executed every time the page loads. From this point on, the possible damage that could be done is endless and only limited by the attacker’s imagination... well, and their coding skills.

New-school apps

In the first example I gave, when you updated the email address on the contact page and the request was fulfilled by the back end, the entire page would reload in order to display the newly created or updated information. You can see how inefficient this is, especially if the only thing changing on the page is a single line or a few lines of text. Here is where ajax, and/or the fetch method, comes in.

Ajax, or the fetch method, can be used to get data from or post data to a remote source, then update the front-end UI of that web application without having to refresh the page. Only the content from the specific request is updated, not the entire page, and that is the key difference between our first example and this one.

And a very popular format for said data being sent and received is JavaScript Object Notation, most commonly known as JSON. (Don't worry, I’ll get back to those curly braces in just a bit.)

New-school XSS

(Well, not really, but it sounds cool.)

Now, let's pretend we’ve traveled back to the future and our contact page has been rewritten to use ajax or the fetch method to send and receive data to and from the database. From the user's point of view, nothing has changed — still the same old form. But this time, when the email address is being updated, only the contact form refreshes. The entire page and all of its contents do not refresh like in the previous version, which is a major win for efficiency and user experience.

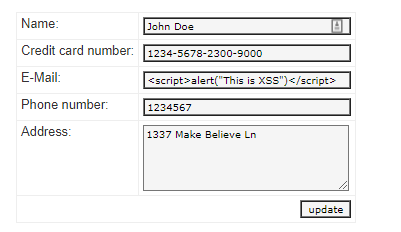

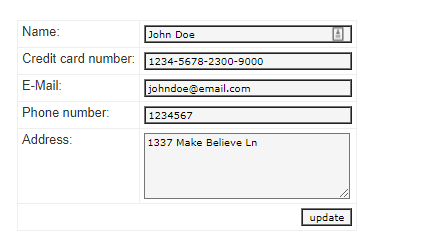

Below is an example of what a POST might look like formatted in JSON.

“What is JSON?” you might ask. Short for JavaScript Object Notation, it is a lightweight text format for storing and transferring data and is most commonly used when sending data to and from servers. Remember those curly braces I mentioned earlier? Well, one quick and easy way to spot JSON is the formatting and the use of curly braces.

In the example above, you can see what our new POST looks like using ajax or the fetch method in JavaScript. While the end result is no different than before, as seen in the example below, the method that was used to update the page is quite different. The key difference here is that the data we want to update is being treated as just that: data, but in the form of JSON as opposed to HTML.

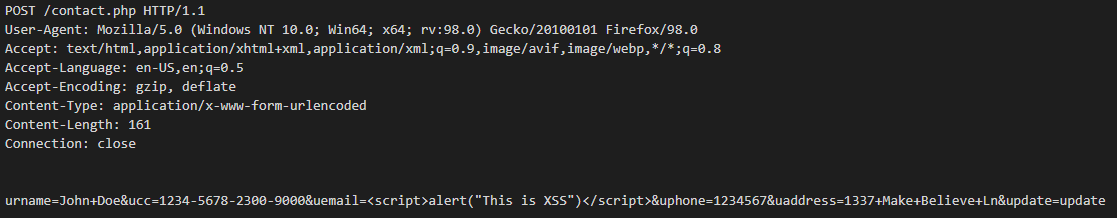

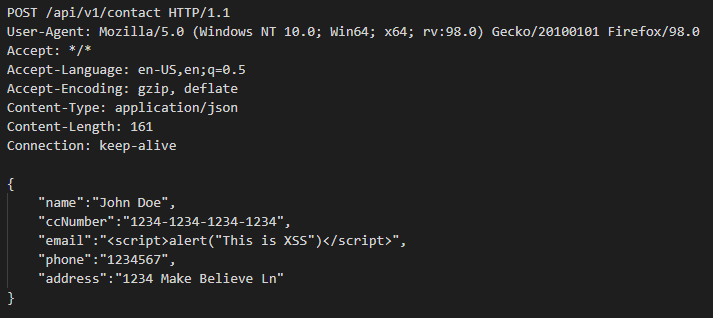

Now, let's inject the same XSS payload into the same email field and hit update. In the example below, you can see that our POST request has been wrapped in curly braces, using JSON, and is formatted a bit differently than it was previously, before being sent to the back end to be processed.

In the example above, you can see that the application is allowing my email address to be the XSS payload in its entirety. However, the JavaScript here is only being displayed and not being executed as code by the browser, so the alert “pop” message never gets triggered as in the previous example. That again is the key difference from the original way we were fulfilling the requests versus our new, more modern way — or in short, using JSON instead of HTML.

Now, you might be asking yourself, "What's wrong with allowing the XSS payload to be the email address if it's only being displayed and not being executed as JavaScript by the browser?" That is a valid question, but hear me out.

See, I've been working in this industry long enough to know that the two most common responses to a question or statement regarding cybersecurity begin with either “that depends…” or “what if…” I'm going to go with the latter here and throw a couple what-ifs at you.

Now that my XSS is stored in your database, it’s only a matter of time before this ticking time bomb goes off. Just because my XSS is being treated as JSON and not HTML now does not mean that will always be the case, and attackers are betting on this.

Here are a few scenarios.

Scenario 1

What if team B handles this data differently from team A? What if team B still uses more traditional methods of sending and receiving data to and from the back end and does leverage the use of HTML and not JSON?

In that case, the XSS would most likely eventually get executed. It might not affect the website that the XSS was originally injected into, but the stored data can be (and usually is) also used elsewhere. The XSS stored in that database is probably going to be shared and used by multiple other teams and applications at some point. The odds of all those different teams leveraging the exact same standards and best practices are slim to none, and attackers know this.

Scenario 2

What if, down the road, a developer using more modern techniques like ajax or the fetch method to send and receive data to and from the back end decides to use the .innerHTML property instead of .innerTEXT to load that JSON into the UI? All bets are off, and the stored XSS that was previously being protected by those lovely curly braces will now most likely get executed by the browser.

Scenario 3

Lastly, what if the current app had been developed to use server-side rendering, but a decision from higher up has been made that some costs need to be cut and that the company could actually save money by recoding some of their web apps to be client-side rather than server-side?

Previously, the back end was doing all the work, including sanitizing all user input, but now the shift will be for the browser to do all the heavy lifting. Good luck spotting all the XSS stored in the DB — in its previous state, it was “harmless,” but now it could get rendered to the UI as HTML, allowing the browser to execute said stored XSS. In this scenario, a decision that was made upstream will have an unexpected security impact downstream, both figuratively and literally — a situation that is all too well-known these days.

Final thoughts

Part of my job as a security advisor is to, well, advise. And it's these types of situations that keep me up at night. I come across XSS in applications every day, and while I may not see as many fun and exciting “pops” as in years past, I see something a bit more troubling.

This type of XSS is what I like to call a “sleeper vuln” – laying dormant, waiting for the right opportunity to be woken up. If I didn't know any better, I'd say XSS has evolved and is aware of its new surroundings. Of course, XSS hasn’t evolved, but the applications in which it lives have.

At the end of the day, we’re still talking about the same XSS from its conception, the same XSS that has been on the OWASP Top 10 for decades — what we’re really concerned about is the lack of sanitization or handling of user input. But now, with the massive adoption of JavaScript frameworks like Angular, libraries like React, the use of APIs, and the heavy reliance on them to handle the data properly, we’ve become complacent in our duties to harden applications the proper way.

There seems to be a division in camps around XSS in JSON. On the one hand, some feel that since the JavaScript isn't being executed by the browser, everything is fine. Who cares if an email address (or any data for that matter) is potentially dangerous — as long as it's not being executed by the browser. And on the other hand, you have the more fundamentalist, dare I say philosophical thought that all user input should never be trusted. It should always be sanitized, regardless of whether it’s treated as data or not — and not solely because of following best coding and security practices, but also because of the “that depends” and “what if” scenarios in the world.

I'd like to point out in my previous statement above, that “as long as” is vastly different from “cannot.” “As long as” implies situational awareness and that a certain set of criteria need to be met for it to be true or false, while “cannot” is definite and fixed, regardless of the situation or criteria. “As long as the XSS is wrapped in curly braces” means it does not pose a risk in its current state but could in other states. But if input is sanitized and escaped properly, the XSS would never exist in the first place, and thus it “cannot” or could not be executed by the browser, ever.

I guess I cannot really complain too much about these differences of opinions. The fact that I'm even having these conversations with others is already a step in the right direction. But what does concern me is that it's 2022, and we’re still seeing XSS rampant in applications, but the fact that it's wrapped in JSON somehow makes it acceptable. One of the core fundamentals of my job is to find and prioritize risk, then report. And while there is always room for discussion around the severity of these types of situations, lots of factors have to be taken into consideration: A spade isn't always a spade in application security, or cybersecurity in general for that matter. But you can rest assured if I find XSS in JSON in your environment, I will be calling it out.

I hope there will be a future where I can look back and say, “Remember that one time when curly braces were all that prevented your website from getting hacked?” Until then, JSON or not, never trust user data, and sanitize all user input (and output, for that matter). A mere { } should never be the difference between your site getting hacked or not.

Additional reading:

- Cloud-Native Application Protection (CNAPP): What's Behind the Hype?

- Rapid7 Named a Visionary in 2022 Magic Quadrant™ for Application Security Testing Second Year in a Row

- Let's Dance: InsightAppSec and tCell Bring New DevSecOps Improvements in Q1

- Securing Your Applications Against Spring4Shell (CVE-2022-22965)

NEVER MISS A BLOG

Get the latest stories, expertise, and news about security today.

Subscribe