Welcome to the NICER Protocol Deep Dive blog series! When we started researching what all was out on the internet way back in January, we had no idea we'd end up with a hefty, 137-page tome of a research report. The sheer length of such a thing might put off folks who might otherwise learn a thing or two about the nature of internet exposure, so we figured, why not break up all the protocol studies into their own reports?

So, here we are! What follows is taken directly from our National / Industry / Cloud Exposure Report (NICER), so if you don't want to wait around for the next installment, you can cheat and read ahead!

DNS-over-TLS (DoT) (TCP/853)

Encrypting DNS is great! Unless it's baddies doing the encrypting.

TLDR

- WHAT IT IS: DNS over TLS is just what it says on the tin: the DNS protocol embedded in a TLS connection, ostensibly to make your DNS request more confidential.

- HOW MANY: 3,237 discovered nodes. A hodgepodge mix of vendor/version information was discernible, but you’ll need to read the details to find out more.

- VULNERABILITIES: Whatever is in the DNS that backs the service or in the code that presents TLS (more often than not, a plain, ol’ web server).

- ADVICE: It’s complicated (read on to find out why!)

- ALTERNATIVES: Plain, simple, uncomplicated, and woefully unconfidential UDP DNS; DNS over HTTPS (DoH); DNS over QUIC (DoQ); DNS over avian carriers (DoAC).

- GETTING: Drunk with power. There are nearly two times as many as April 2019.

At face value, DNS over TLS (henceforth referred to as DoT) aims to be the confidentiality solution for a legacy cleartext protocol that has managed to resist numerous other confidentiality (and integrity) fixup attempts. It is one of a handful of modern efforts to help make DNS less susceptible to eavesdropping and person-in-the-middle attacks.

Discovery details

We chose to examine DoT because web browsers have become the new operating system of the internet, and DoT and cousins all allow browsers (or any app, really) to bypass your home, ISP, or organization’s choices of DNS resolution method and resolution provider. Since it’s presented over TLS, it can also be a great way for attackers to continue to use DNS as a command-and-control channel as well as an exfiltration channel.

We chose to examine DoT versus DoH because, well, it is far easier to enumerate DoT endpoints than it is DoH endpoints. It’s getting easier to enumerate DoH since there seems to be some agreement on the standard way to query it, so that will likely make it to a future report, but for now, let’s take a look at what DoT Project Sonar found:

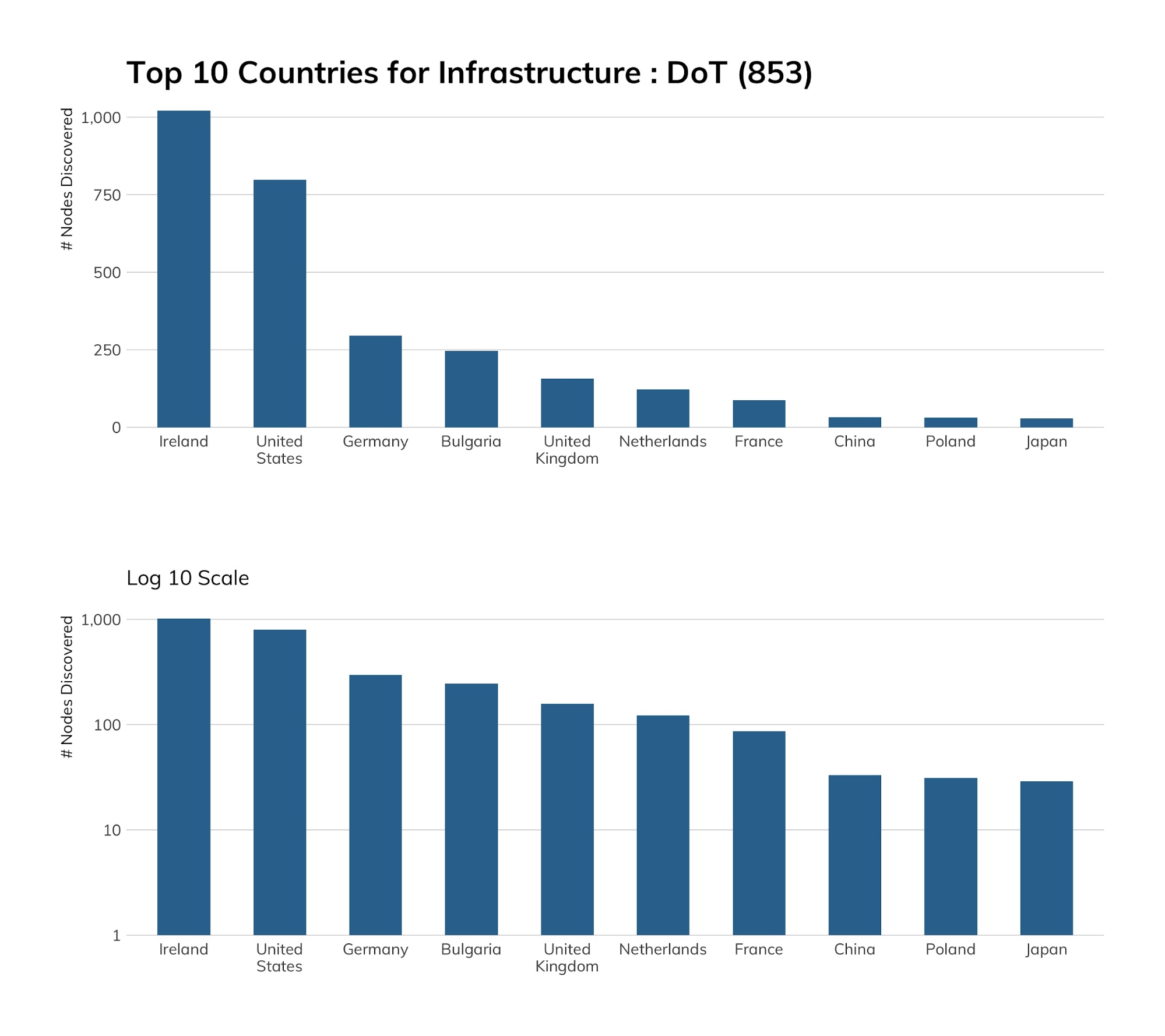

Yes, you read that chart correctly! Ireland is No. 1 in terms of the number of nodes running a DoT service, and it’s all thanks to a chap named Daniel Cid, who co-runs CleanBrowsing, which is a “DNS-based content filtering service that offers a safe way to browse the web without surprises.” Daniel has his name on AS205157, which is allocated to Ireland, but the CleanBrowsing service itself is run out of California. In fact, CleanBrowsing comprises almost 50% of the DoT corpus (1,612 nodes), with 563 nodes attributed to the United States and a tiny number of servers attributed to a dozen or so other country network spaces.

Both the U.S. and Germany have a cornucopia of server types and autonomous systems presenting DoT services (none really stand out besides CleanBrowsing).

Since Bulgaria rarely makes it into top 10 exposure lists, we took a look at what was there and it’s a ton (relatively, anyway: 242) of DoT servers in Fiber Optics Bulgaria OOD, which is a kind of “meta” service provider for ISPs. Given the relative scarcity of IPv4 addresses, setting aside 242 of them just for DoT is a pretty major investment.

Even though the numbers are small, Japan’s presence is interesting, as it’s nearly all due to a single ISP: Internet Initiative Japan Inc.

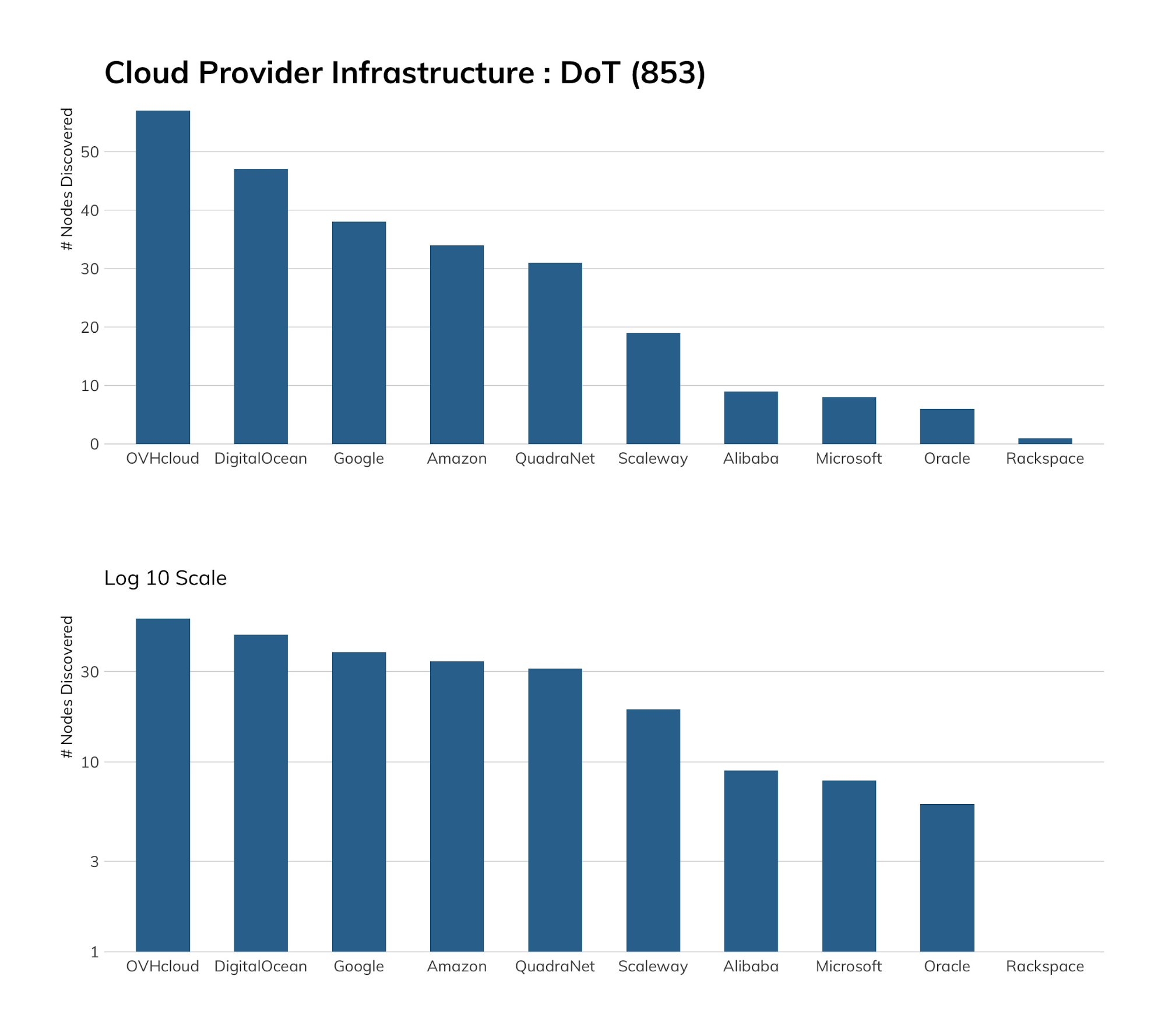

In case you have been left unawares, Google is a big player] in the DoT space, but it tends to concentrate DNS exposure to a tiny handful of IP addresses (i.e., that bar is not Google-proper). When we filter out CleanBrowsing (yep, they’re everywhere), we’re left with the major exposure in Google being … a couple dozen servers running an instance of Pi-hole (dnsmasq-pi-hole-2.80, to be precise). Cut/paste that finding for OV and DigitalOcean and yep, that same Pi-hole setup is tops in those two clouds as well.

You don’t need to get all fancy and run a Pi-hole setup to host your own DoT server. Just fire up an nginx instance, create a basic configuration, set up your own DNS behind it, and now, you too can stop your ISP from snooping your DNS queries.

Exposure information

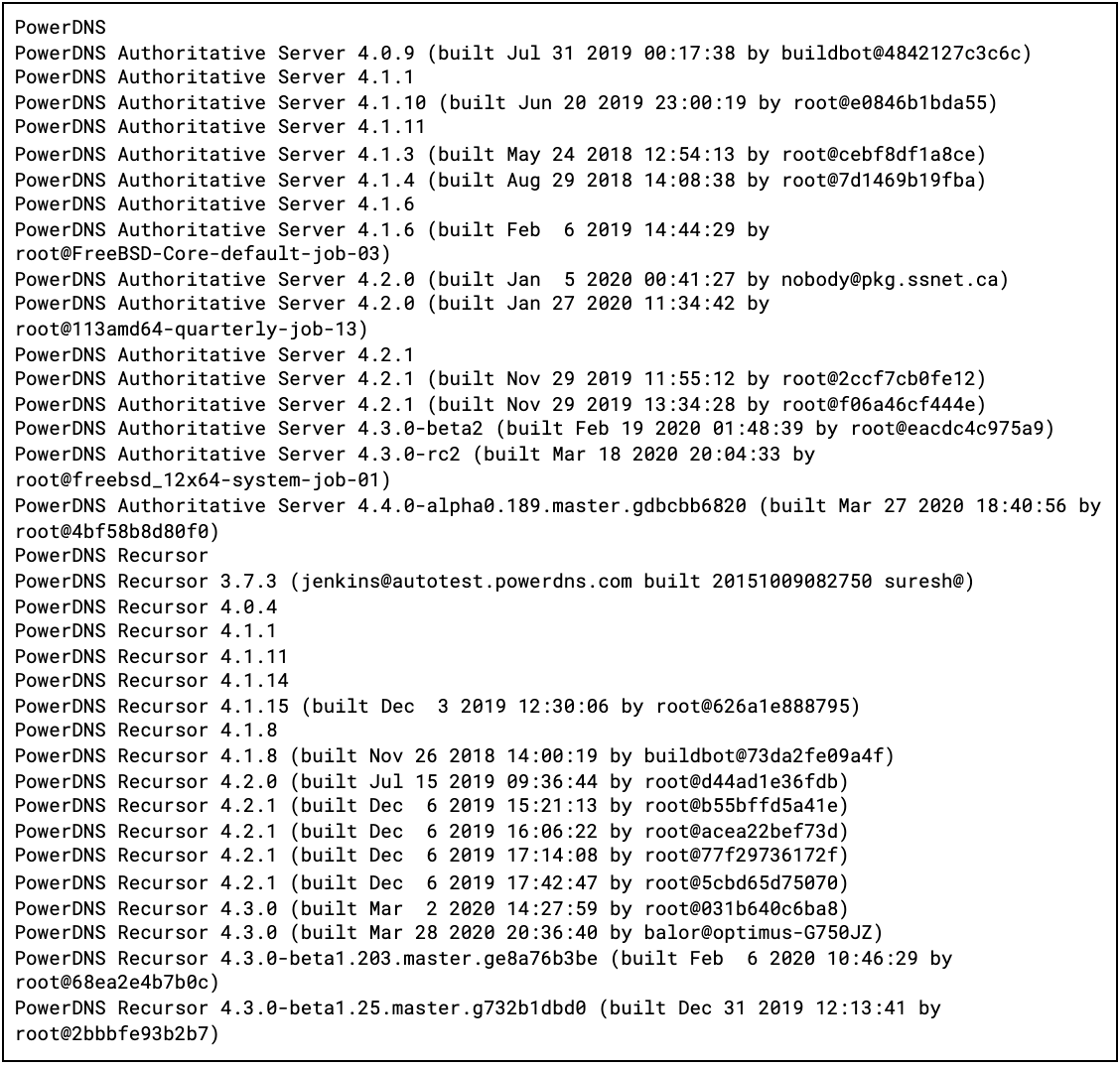

Here is where we’d normally talk about versions and CVEs, etc., but the DoT situation is complicated by a few things. First, we have big players in this space using proprietary solutions, so version fingerprints such as “CleanBrowsing v1.6a” are not very useful information. Second, should we focus on the version of the web server or of the back-end DNS server (or, both)? The latter might not be useful, since you can configure an nginx DoT setup to proxy to a third party, and that’s what will get picked up in the response. Lastly, even if we focus on the second-tier “big guns,” such as PowerDNS, we end up with a situation like this:

Giving you that glimpse does help to show it’s utter chaos even in PowerDNS-land, but DNS and chaos seem to go hand in hand.

Attacker’s view

There are no DoT honeypots in Project Lorelei, but DoT is just a TLS wrapper over a traditional DNS binary-format query. When we looked for that in the TCP/853 full packet captures, we saw us (!) and a couple other researchers. Not very exciting, but with the goal of DoT being privacy, we really shouldn’t see random DoT requests.

Attackers are more likely to stand up their own DoT servers or reconfigure other DoT servers to use their DNS back-ends and then use those as covert channels once they gain a foothold after a successful phishing attack. This is a big reason we enumerate/catalog DoT, and we’re starting to see more DoT in residential ISP space and traditional hosting provider IP space. It looks like more folks are experimenting with DoT with each monthly study.

Our advice

IT and IT security teams should block TCP/853, lock down DoT and DoH browser settings as much as possible so there is no way to bypass organizational IT policies, and monitor for all attempts to use DoT or DoH services internally (or externally). In other words, unless you’re the ones setting them up, disallowing rogue, internal DoT is the safest course.

Cloud providers should consider offering managed DoT solutions and provide patched, secure disk images for folks who want to stand up their own. (This is one of the few cases where organizational advice and cloud advice are quite nearly opposite.)

Government cybersecurity agencies should monitor for malicious use of DoT and provide timely updates to the public. These centers should also be a source of unbiased, expert information on DoT, DoH, DoQ (et al).